Uganda’s Big Seven Safaris- The Ultimate Wildlife Experience

Uganda has quietly orchestrated one of Africa’s most remarkable conservation and tourism success stories. While East African neighbors Kenya and Tanzania have long dominated the safari circuit with their sweeping savannas and the iconic Big Five, Uganda has carved out a unique niche by adding two extraordinary primates to the traditional lineup—mountain gorillas and chimpanzees—creating what is now celebrated as the “Big Seven” safari experience.

This evolution represents more than just clever marketing. It reflects decades of conservation commitment, ecological diversity, and a profound understanding that Uganda’s greatest wildlife treasures extend beyond the savanna megafauna to include our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom.

The Big Five Legacy and Uganda’s Bold Addition

The term “Big Five”—lions, elephants, leopards, buffaloes, and rhinos—originated not from conservation biology but from colonial-era big game hunting. These animals earned their dangerous reputation among hunters, becoming the most prized and perilous trophies. As safari tourism evolved from hunting to photography, the Big Five remained the gold standard for wildlife experiences across Africa.

Uganda possesses all five of these iconic species, but what truly distinguishes the country is its incredible primate diversity. Home to over half of the world’s remaining mountain gorillas and robust chimpanzee populations, Uganda recognized an opportunity to redefine the African safari paradigm. The Big Seven concept emerged organically, acknowledging that encountering a silverback gorilla in the misty mountains or a chimpanzee community in their forest realm rivals any encounter with traditional safari animals in terms of emotional impact and conservation significance.

Uganda’s Ecological Tapestry: Where Forests Meet Savannas

Uganda’s geographical position—straddling the equator at the convergence of East and Central Africa—creates an extraordinary mosaic of ecosystems compressed into a relatively compact area. This “Pearl of Africa,” as Winston Churchill famously called it, contains sprawling savannas, impenetrable rainforests, snow-capped mountains, vast wetlands, and the source of the Nile River.

This ecological diversity enables Uganda to support both savanna megafauna and forest primates within a single country, often in close proximity. A visitor can track mountain gorillas in Bwindi Impenetrable Forest one day and watch lions climbing trees in Queen Elizabeth National Park the next—a combination impossible in most African destinations.

The western arm of the Great Rift Valley dominates Uganda’s landscape, creating fertile valleys, crater lakes, and the dramatic escarpments that define parks like Queen Elizabeth and Murchison Falls. These varied habitats support an astonishing 1,080 bird species (more than half of Africa’s total), 343 mammal species, and 142 reptile species, making Uganda one of the most biodiverse countries on the continent.

The Big Seven: Species by Species

Mountain Gorillas: The Crown Jewel

No wildlife encounter matches the profound emotional resonance of sitting meters away from a mountain gorilla family. These gentle giants, sharing 98% of our DNA, display remarkably human-like behaviors—playful juveniles tumbling over each other, protective mothers cradling infants, and massive silverbacks exuding quiet authority.

Uganda harbors over 480 mountain gorillas—approximately half the global population of roughly 1,000 individuals. These populations inhabit two primary locations: Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, with about 459 gorillas across 21 habituated groups, and Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, home to one habituated group that occasionally crosses into neighboring Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The gorilla tracking experience in Uganda differs significantly from other activities. Limited to just eight visitors per gorilla family per day, these intimate encounters generate substantial revenue—permits cost $800 for foreign non-residents in peak season—while maintaining minimal disturbance to the animals. This high-value, low-impact model has proven remarkably successful, with gorilla numbers steadily increasing even as tourism grows.

Chimpanzees: Our Closest Living Relatives

While gorillas capture headlines, Uganda’s chimpanzee populations represent an equally significant conservation achievement. The country hosts approximately 5,000 chimpanzees distributed across multiple forest reserves and national parks, making it one of Africa’s prime destinations for chimpanzee tracking.

Kibale National Park stands as the chimpanzee capital of the world, with the highest density of these great apes anywhere—an estimated 1,500 individuals within its 795 square kilometers of tropical rainforest. The park’s Kanyanchu community has been habituated for research and tourism since 1993, offering visitors exceptional viewing opportunities.

Chimpanzee encounters provide a different but equally compelling experience compared to gorillas. These highly intelligent, social animals are more active and vocal, often engaging in dramatic displays, complex social interactions, and remarkable tool use. Watching chimpanzees hunt, groom, or communicate reveals cognitive abilities that challenge our understanding of consciousness and culture in non-human species.

Beyond Kibale, chimpanzees can be tracked in Budongo Forest (Murchison Falls National Park), Kyambura Gorge (Queen Elizabeth National Park), Kalinzu Forest, and Semliki Wildlife Reserve, providing multiple opportunities throughout the country.

Lions: The Savanna Kings

Uganda’s lion populations faced near-extinction in the early 2000s due to habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, and disease. The species’ dramatic recovery exemplifies successful conservation intervention. Today, approximately 400-500 lions roam Uganda’s savannas, with significant populations in Queen Elizabeth National Park, Murchison Falls National Park, and Kidepo Valley National Park.

Queen Elizabeth National Park offers one of Africa’s most unusual lion behaviors—tree-climbing lions in the Ishasha sector. While lions occasionally climb trees in various locations, the Ishasha prides have made this behavior habitual, possibly to escape ground heat and biting insects while gaining a vantage point for spotting prey. These sightings have become iconic, with lions draped majestically across fig tree branches.

The Uganda Carnivore Program and Uganda Wildlife Authority have implemented innovative conservation strategies, including lion tracking collars, community education programs, and predator-proof livestock enclosures, helping reduce conflict and stabilize populations.

Elephants: The Ecosystem Engineers

Uganda supports approximately 5,000 elephants, primarily concentrated in four major parks: Murchison Falls (1,330), Kidepo Valley (650), Queen Elizabeth (2,500), and smaller populations in Kibale and other protected areas. These savanna elephants play crucial roles as ecosystem engineers, creating waterholes, dispersing seeds, and maintaining habitat structure.

The elephant populations in Uganda have rebounded significantly from poaching lows in the 1980s and 1990s. Murchison Falls National Park, bisected by the Victoria Nile, provides spectacular elephant viewing along the river banks, particularly at the Paraa area where herds congregate to drink and bathe.

Conservation challenges persist, including human-elephant conflict in agricultural areas bordering parks and occasional poaching for ivory. However, strengthened anti-poaching units, community-based conservation programs, and wildlife corridors have contributed to relatively stable populations.

Leopards: The Elusive Shadows

As Africa’s most widespread big cat, leopards inhabit nearly every Ugandan national park, yet remain the most challenging of the Big Seven to spot. Their solitary, nocturnal nature and exceptional camouflage make sightings relatively rare, though not impossible.

Queen Elizabeth National Park, particularly the Mweya Peninsula and Kasenyi plains, offers the best leopard viewing opportunities. Night game drives, permitted in select parks, significantly increase chances of encounters. The cats are also regularly spotted in Kidepo Valley National Park and Murchison Falls.

Leopards demonstrate remarkable adaptability, thriving in habitats from dense forests to open savannas. Their diet diversity—over 90 documented prey species—enables them to persist even in human-modified landscapes where other large predators struggle.

Buffaloes: The Unpredictable Herds

African buffaloes, considered by many as the most dangerous of the Big Five, roam Uganda’s savannas in impressive numbers. Queen Elizabeth National Park alone hosts approximately 10,000 buffaloes, with additional thousands in Murchison Falls, Kidepo Valley, and Lake Mburo National Park.

These massive bovines display complex social structures, with breeding herds of females and young sometimes exceeding 1,000 individuals. Bachelor males form smaller groups or become solitary “dagga boys”—older bulls often caked in mud—that earned reputations among hunters as particularly aggressive.

Buffalo viewing in Uganda includes dramatic encounters along the Kazinga Channel in Queen Elizabeth National Park, where massive herds gather at water’s edge, creating spectacular photography opportunities. The interaction between buffaloes and predators, particularly lions, provides some of the most dynamic wildlife moments.

Rhinos: The Conservation Comeback

Rhinos represent Uganda’s greatest conservation comeback story within the Big Seven narrative. By 1983, both black and white rhinos had been completely eradicated from Uganda through poaching. The country’s wildlife heritage seemed permanently diminished.

The establishment of the Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary in 2005 marked a determined effort to return rhinos to Uganda. Located approximately 176 kilometers north of Kampala along the route to Murchison Falls, Ziwa has successfully bred and raised southern white rhinos in a semi-wild environment. The sanctuary now hosts over 40 rhinos, with the population steadily increasing.

Rhino tracking at Ziwa on foot provides an intimate experience with these prehistoric-looking megaherbivores. Rangers guide visitors within safe distances of the rhinos, explaining individual personalities, conservation challenges, and the eventual goal of reintroducing rhinos into national parks once populations reach sustainable numbers.

While rhino numbers remain modest compared to the other Big Seven species, their presence symbolizes Uganda’s conservation commitment and provides hope for future range expansion.

The Parks: Where to Experience the Big Seven

Queen Elizabeth National Park: The Big Seven Hub

Queen Elizabeth National Park arguably offers the most comprehensive Big Seven experience within a single destination. This 1,978-square-kilometer park contains ten primate species (including chimpanzees in Kyambura Gorge), tree-climbing lions in Ishasha, substantial elephant and buffalo populations, and regular leopard sightings.

The park’s diversity stems from its ecological variety—savanna grasslands, wetlands, lowland forests, and crater lakes. The Kazinga Channel, connecting Lakes Edward and George, provides exceptional game viewing with the highest concentration of hippos in Africa and enormous crocodiles basking on the banks.

Murchison Falls National Park: Where the Nile Explodes

Uganda’s largest national park (3,893 square kilometers) showcases the raw power of nature where the Victoria Nile forces through a narrow gorge, creating the thunderous Murchison Falls. This dramatic landscape supports significant populations of lions, elephants, buffaloes, and leopards.

The northern bank of the Nile offers classic savanna game viewing, while Budongo Forest on the southern edge provides chimpanzee tracking. A boat safari to the falls base combines spectacular scenery with wildlife viewing—elephants, hippos, crocodiles, and numerous water birds along the riverbanks.

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park: The Gorilla Sanctuary

This UNESCO World Heritage Site protects approximately 331 square kilometers of mountainous rainforest, home to roughly half the world’s mountain gorillas. Bwindi’s ancient forest, over 25,000 years old, represents one of Africa’s most biologically diverse ecosystems, with 120 mammal species, 350 bird species, and 310 butterfly species.

Gorilla tracking in Bwindi involves hiking through steep, dense vegetation—challenging but profoundly rewarding. The park’s four sectors (Buhoma, Ruhija, Rushaga, and Nkuringo) each offer distinct tracking experiences and various habituated gorilla families.

Kibale National Park: The Primate Paradise

With 13 primate species, Kibale holds the highest concentration of primates in East Africa. Beyond its champion chimpanzee population, the park hosts red colobus, L’Hoest’s monkeys, blue monkeys, grey-cheeked mangabeys, red-tailed monkeys, black-and-white colobus, and the nocturnal pottos and galagos.

The park offers both standard chimpanzee tracking and a more intensive “Habituation Experience,” where visitors spend an entire day with researchers and a chimpanzee community, observing the lengthy process of habituating wild apes to human presence.

Kidepo Valley National Park: The Remote Wilderness

Tucked into Uganda’s remote northeastern corner bordering South Sudan and Kenya, Kidepo Valley offers perhaps East Africa’s most authentic wilderness experience. Its isolation has preserved both wildlife and traditional cultures, with the pastoral Karamojong and Ik people maintaining ancient lifestyles around the park.

Kidepo’s 1,442 square kilometers of rugged savanna support impressive populations of lions, elephants, and buffaloes, plus species found nowhere else in Uganda—cheetahs, bat-eared foxes, caracals, and aardwolves. The dramatic landscapes of Narus Valley and the seasonal Kidepo River create stunning backdrops for game viewing.

Conservation Success: From Crisis to Recovery

Uganda’s Big Seven story is fundamentally a conservation narrative. In the 1970s and 1980s, political instability and civil conflict devastated wildlife populations. Poaching ran virtually unchecked, and several species neared local extinction. By the late 1980s, rhinos had been eliminated, elephant numbers had crashed from an estimated 30,000 to perhaps 2,000, and gorilla populations faced existential threats from habitat loss and cross-border instability.

The turnaround began with political stabilization in 1986 and the establishment of the Uganda Wildlife Authority in 1996. Several factors contributed to recovery:

Community-Based Conservation: Recognition that local communities must benefit from wildlife led to revenue-sharing programs. Around many parks, 20% of gate fees support community projects—schools, health clinics, and infrastructure. This alignment of conservation with community welfare has reduced poaching and increased local support for protected areas.

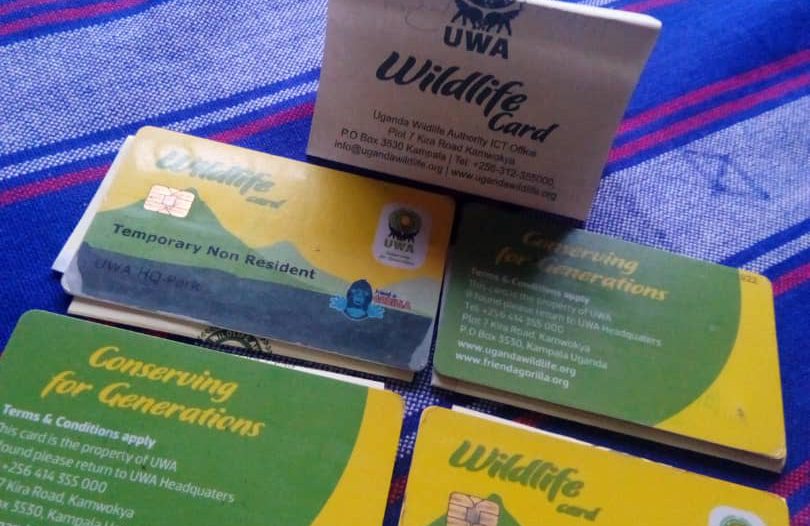

Gorilla Tourism Management: The strict regulation of gorilla tourism—limited permits, habituated groups, trained guides, and strict protocols—demonstrated that wildlife could generate substantial sustainable revenue. Gorilla permit fees have increased over time (from $350 in 2005 to $800 currently), reflecting both demand and the need to fund conservation while limiting visitor numbers.

Anti-Poaching Investments: Professionalization of ranger forces, improved equipment and training, intelligence-led operations, and partnership with international conservation organizations strengthened protection. The Uganda Wildlife Authority now employs over 800 rangers across the protected area network.

Translocation and Reintroduction: The Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary project demonstrated feasibility of reintroducing locally extinct species. Similar approaches have moved problem elephants from human conflict zones to parks with lower populations, reducing both human-wildlife conflict and consolidating conservation efforts.

Research and Monitoring: Long-term research programs, particularly for great apes, provide essential data for management decisions. The Kibale Chimpanzee Project, ongoing since 1987, represents one of the world’s longest continuous primate studies.

The Tourism Model: High Value, Low Impact

Uganda has deliberately pursued a “high-value, low-impact” tourism model, particularly for primate encounters. Rather than maximizing visitor numbers, the strategy emphasizes premium experiences with minimal ecological disturbance.

Gorilla permits at $800 represent significant investment for travelers but generate crucial conservation funding. With 21 habituated groups in Bwindi and one in Mgahinga, each allowing eight visitors daily, maximum daily capacity reaches approximately 176 permits. This controlled access prevents overcrowding, reduces stress on gorillas, and ensures quality experiences.

Chimpanzee tracking follows similar principles, though permits cost less ($200-250) and group sizes are slightly larger. The combination of relatively high fees with limited permits creates sustainable funding streams while maintaining animal welfare standards.

This model contrasts with mass-market safari approaches in some African destinations, where vehicle congestion around wildlife can diminish both visitor experience and animal welfare. Uganda’s approach particularly suits great ape tourism, where respiratory disease transmission remains a concern and behavioral disturbance can have long-term consequences.

Challenges and Threats

Despite remarkable successes, Uganda’s Big Seven species face ongoing challenges:

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Uganda ranks among Africa’s most densely populated countries, with over 48 million people. Agricultural expansion, settlements, and infrastructure development continually pressure protected area boundaries. Wildlife corridors between parks have narrowed or disappeared, isolating populations and restricting migration routes.

Human-Wildlife Conflict: As human populations expand into wildlife areas, conflicts intensify. Elephants raid crops, causing significant economic losses to smallholder farmers. Lions occasionally kill livestock. Buffaloes damage fields. These conflicts generate local resentment toward wildlife and conservation efforts.

Disease: Great apes share susceptibility to human diseases. Respiratory infections from tourists or researchers can devastate gorilla or chimpanzee communities with limited immunity. COVID-19 underscored these concerns, leading to temporary tourism closures and renewed emphasis on health protocols.

Poaching: While significantly reduced from historical levels, poaching persists—sometimes for bushmeat, occasionally for ivory, and rarely for live animal trade. Snares set for small game often injure or kill larger species.

Climate Change: Shifting rainfall patterns, temperature increases, and habitat changes affect all species. Mountain gorillas, adapted to cool montane forests, face particular vulnerability as their highland habitats warm.

Political and Economic Instability: Regional instability, particularly in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan, can spill across borders, affecting both wildlife and tourism. Economic pressures may tempt governments to prioritize short-term resource exploitation over long-term conservation.

The Economic Impact

Wildlife tourism generates substantial revenue for Uganda, though precise figures fluctuate with global conditions. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism contributed approximately $1.6 billion to Uganda’s GDP and employed hundreds of thousands directly and indirectly.

Gorilla tourism alone generates tens of millions annually. With permits at $800 and approximately 70% occupancy in typical years, Bwindi and Mgahinga produce over $35 million in direct permit revenue, not including associated spending on accommodation, transport, guides, and services.

The economic argument for conservation grows increasingly compelling as decision-makers recognize wildlife’s long-term value. A single gorilla family can generate hundreds of thousands of dollars annually through tourism—far exceeding any extractive use of their habitat. This economic reality, combined with Uganda’s international reputation as a conservation destination, provides powerful incentives for continued protection.

The Future: Expansion and Innovation

Uganda’s conservation trajectory points toward several emerging developments:

Rhino Reintroduction: Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary always intended as a breeding ground for eventual reintroduction into national parks. With populations now exceeding 40 individuals, discussions about moving rhinos to Murchison Falls or other protected areas are advancing. These reintroductions would complete true Big Seven safari opportunities within national park settings.

Corridor Restoration: Recognizing that isolated populations face genetic risks and limited range, efforts to restore wildlife corridors between parks are gaining traction. The challenge involves balancing human land use with wildlife movement, requiring creative solutions like wildlife-friendly farming practices and compensation schemes.

Technology Integration: Conservation increasingly employs technology—GPS collars for tracking animal movements, camera traps for population monitoring, drones for anti-poaching surveillance, and genetic analysis for population management. These tools improve both conservation outcomes and visitor experiences.

Expanded Access: Infrastructure improvements, including roads and airstrips, make remote parks like Kidepo increasingly accessible. While this expands tourism opportunities and economic benefits, it requires careful management to prevent overcrowding and habitat degradation.

Climate Adaptation: Conservation planning must incorporate climate change scenarios. For mountain gorillas, this might mean protecting higher-elevation forests as buffers. For elephants, ensuring water access during extended dry periods becomes critical.

Beyond the Big Seven: Uganda’s Broader Wildlife Heritage

While the Big Seven concept provides powerful marketing and conservation focus, Uganda’s wildlife wealth extends far beyond these iconic species. The country hosts over 20 primate species, including the endangered Uganda red colobus, the graceful black-and-white colobus, and numerous monkey species.

Birdwatchers consider Uganda among Africa’s premier destinations, with species ranging from the prehistoric-looking shoebill stork in wetlands to the vibrant great blue turaco in forests. Murchison Falls alone records over 450 bird species.

The lesser-known carnivores—spotted hyenas, side-striped jackals, servals, African civets, and various mongoose species—play crucial ecological roles. The savanna parks support numerous antelope species: Uganda kobs (the national antelope), Jackson’s hartebeests, topis, oribis, bushbucks, waterbucks, and reedbucks.

This biodiversity underpins the Big Seven experience, creating rich, complex ecosystems that engage visitors beyond checklist mentality toward deeper ecological understanding.

The Cultural Dimension

Uganda’s Big Seven safari experience intertwines with rich cultural heritage. Multiple ethnic groups—Batwa, Bakiga, Banyankole, Batooro, and others—live around the parks, maintaining traditions shaped by centuries of coexistence with wildlife.

The Batwa people, often called “pygmies,” traditionally lived as hunter-gatherers in the forests now protected as Bwindi and Mgahinga. Their displacement when parks were established raises complex questions about conservation and indigenous rights. Today, Batwa cultural experiences near the parks provide income while preserving traditional knowledge, though debates continue about adequate compensation and involvement in conservation decision-making.

Cultural encounters—traditional dances, craft markets, village walks, and homestays—enrich the safari experience, contextualizing wildlife within human landscapes and supporting community livelihoods. This integration acknowledges that successful conservation requires addressing human needs alongside species protection.

Practical Considerations for Visitors

Experiencing Uganda’s Big Seven requires planning and realistic expectations. Gorilla and chimpanzee permits must be booked months in advance, particularly during peak seasons (June-September and December-February). Tracking involves hiking through challenging terrain, requiring moderate fitness levels.

Seeing all Big Seven in a single trip is possible but requires at least 10-14 days and careful itinerary planning. A typical comprehensive Big Seven safari might include: Murchison Falls (lions, elephants, leopards, buffaloes, chimpanzees), Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary (rhinos), Kibale (chimpanzees), Queen Elizabeth (lions, elephants, leopards, buffaloes, chimpanzees), and Bwindi (mountain gorillas).

Costs vary widely based on accommodation choices, ranging from budget camping to luxury lodges. Beyond permit fees, daily costs might range from $100-150 for budget travelers to $500+ for luxury experiences. The investment, however, supports conservation directly while providing unforgettable encounters with some of Earth’s most remarkable species.

Conclusion: A Model for African Conservation

Uganda’s Big Seven safari concept represents more than marketing innovation—it exemplifies how conservation can adapt to local ecological realities while generating sustainable economic benefits. By recognizing that Uganda’s unique strength lies in its combination of savanna megafauna and forest primates, conservation planners created a distinctive niche in the competitive safari market.

The success story from near-extinction of multiple species to thriving populations demonstrates that committed conservation, community engagement, and sustainable tourism can reverse even severe wildlife declines. Uganda’s model—high-value experiences, strict regulations, revenue sharing, and professional management—offers lessons for conservation globally.

As travelers increasingly seek meaningful, transformative wildlife encounters rather than mere checklists, Uganda’s intimate, carefully managed approach positions it well for the future. Looking into the eyes of a mountain gorilla, watching a chimpanzee community navigate complex social dynamics, or witnessing a lion pride coordinate a hunt provides profound connections that transcend typical tourism.

The Big Seven concept ultimately celebrates biodiversity in all its forms—from the largest land mammal to our closest evolutionary relatives. In protecting these species and their habitats, Uganda preserves not just individual animals but entire ecosystems, evolutionary processes, and the possibility of wonder for future generations. The rise of Big Seven safaris in Uganda tells a story of hope, demonstrating that with commitment and creativity, conservation and human development can coexist, ensuring that Africa’s extraordinary wildlife heritage endures.

To inquire about or book a Big 7 Uganda safari adventure today- simply contact us now by sending an email to info@rentadriveruganda.com or call us now on +256-700135510.